“Power is not influence. Power is when you have the ability to make change . . . Being speaker of the House, that’s real power.” –Nancy Pelosi

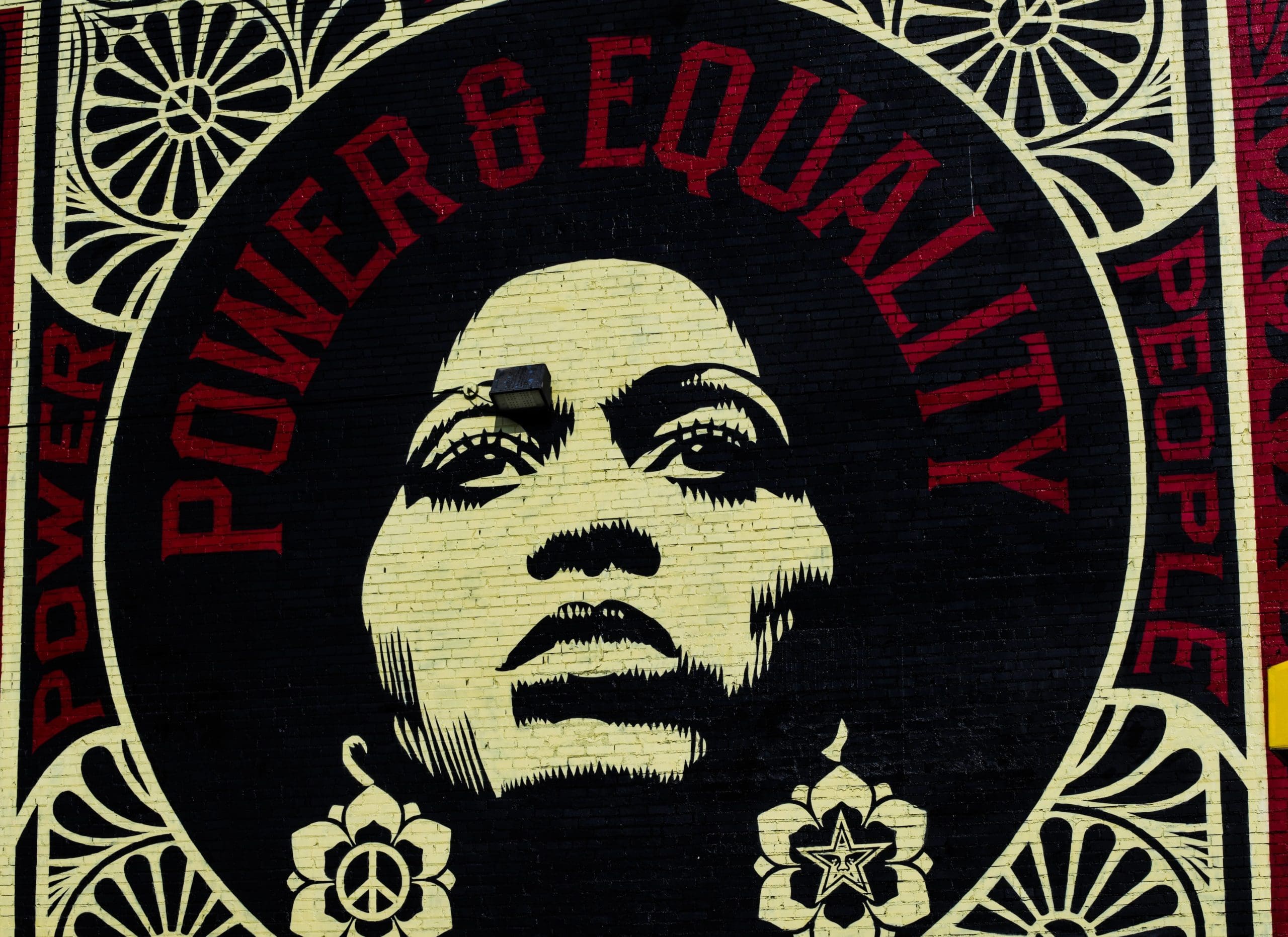

We hear the word influence a lot these days. Celebrities on Instagram, CEOs lobbying in Washington, high-profile political endorsements. In a recent Facebook conversation, culture-maker Kelly Diels discussed influence along with power. Often, the terms get conflated or used interchangeably. But I want to dig into their nuances and differences, and explore how women of color in particular hold, wield, or are subject to each.

Let me start with a story about a difficult conversation.

Influence is Not Power

I sit on the board of my daughter’s school, where I also co-chair the Equity & Inclusion Committee. Often, I find myself in the role of educator, explaining issues of bias and diversity, providing examples, illustrating, demonstrating, and training. Ultimately, what I find myself doing is trying to get others to understand my position, hoping to shape beliefs with my background and expertise, and thereby indirectly influence decisions and actions. This is perhaps why I have often found board meetings challenging and even frustrating.

The work of influencing is draining. It involves the energy-sapping effort of getting people to like and feel comfortable with me instead of exercising the actual power of my experience and expertise. I want to be clear that I’m not maligning influence at all. Influence is necessary to build up credibility, make connections, and find opportunities. Whenever I publish a newsletter, host a retreat, or speak on a podcast, I’m expanding my influence, and proudly so. But I also want to say just as clearly that influence is not the same as power.

In a recent one-on-one conversation with the chairperson of the board, my default behavior of influence became clear to me. I tried to explain my perspective on a decision that I disagreed with. I articulated the common wisdom, hoping he would understand the validity of my view without having to expressly disagree.

Instead he asked me, “Do you want me to make a different choice?”

I said yes.

Then he asked, “Why didn’t you just say what you were thinking?”

It was a good question, one that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since that conversation.

What Stands Between Us and Power is Comfort

Part of the answer is that, more often than not, women of color default to influence because it keeps us safer. What I mean is that we work hard to be believed. We work hard to gain buy-in, to be liked, listened to, and trusted. We work hard to maintain other people’s comfort, often at the expense of showing up as our full selves. We find it unsafe to say exactly what we mean, what we want, or what we need others to do.

This has been my default approach with the board, even though in other areas of my life and career, I am direct, if not blunt, about exercising my power. Working with the board had been so exhausting because it was out of keeping with how I am elsewhere, when I am not consumed by trying to build influence rather than bring my expertise. In truth, I had taken on the role of educator when it was not my responsibility, and no one had ever asked me to do it.

So often, we hope that our education, training, and hard work will open doors for us. But this is not how opportunity is created. Opportunity doesn’t come when we indirectly pull others toward a conclusion and hope that they take the action we want. In fact, usually this leaves us with tremendous anxiety and diminishes our power.

“When I was speaker before, I rarely paid attention to the accoutrements of power. I was just busy being a legislator. This time, people seem to know more about what the speaker is . . . But as I say to the women, nobody ever gives away power. If you want to achieve that, you go for it. But when you get it, you must use it.” –Nancy Pelosi

The Limit of Power is Safety

Throughout history, people of color have not been safe in being direct or trying to exercise power. We know from centuries of experience that when white people get uncomfortable, it gets dangerous for us—not just in terms of bias, but violence and death.

So, we learn to influence. It’s what we do to survive, and it becomes our default way of interacting. We make sure others are comfortable enough with who we are to support our work. We constantly prove our intelligence. We teach and suggest and hope for the outcome we want. Our likeability becomes the measure of our influence. And white people’s comfort remains the limit of our influence.

Here’s a more thorough breakdown of the differences between influence and power.

Influence

- Assumes we are not in a safe environment

- Involves proving our worth and our right to our opinions

- Requires getting others to like us and see us

- Hopes to persuade indirectly

- Is careful not to cause discomfort in others in order to keep us safe

- Is a process of turning our power into something palatable—never angry, disruptive, or confrontational; always deferential and suggestive

- Ultimately leaves decision-making to others and diminishes our power

Power

- The ability to show up authentically with your skills and expertise fully recognized

- Default trust in your judgment

- The expectation that others will listen to your perspective

- Having others do what you say

The Power of Boundaries

When people say “no” to our influence, it can feel devastating, like a personal attack. When our influence is rejected, it feels as though others didn’t like you, believe you, trust you.

When people say “no” to your power, it’s just a “no.” It’s a disagreement with your ideas, a difference of opinion. It’s not personal at all. When you step into power (which is not a rejection of influence), a “no” can be very clarifying. It tells you where others stand, where they’re not willing to go, and what your choices are going forward. A real “no” can highlight important boundaries.

In a recent Leverage to Lead group meeting, some of the women in our group said they would exercise their power more if they knew when they had it. The truth is, your power is always there and it’s always yours. It may not always be safe to use it, but more often we’ve simply been conditioned to be afraid of our power, to be deferential to white supremacy culture’s protection of white people’s comfort because we don’t want to become the scapegoat of white discomfort.

My core message today is that white discomfort is a false boundary. We can stop dancing around or stepping back from discomfort. It is not the limit of our power to express our difference and make change happen. The antidote for this false notion is our own understanding of history, systemic racism, and our personal experience.

The antidote is to stop seeing ourselves as the problem.