It’s affirming to see our Leverage to Lead’s values held by others who are working in DEI and social and racial justice spheres. We feel gratified when we see work that is similarly steeped in humanity, and interpersonal growth.

When we hear Adam Grant say that our culture can understand its values by examining which behaviors get punished and which get rewarded, we celebrate the parallel to our values-based approach.

When we look at Bobbie Harro’s Cycle of Liberation, we resonate with the way she brings to light patterns of behaviors that help us understand our unconscious roles in oppression. Every time we see others emphasizing the slow, personal nature of DEI, our work feels validated.

Today, we want to dig into the parallels between Harro’s Cycle of Liberation and our work at Leverage to Lead. We consistently tell our clients that DEI work isn’t quick. It’s not that we aren’t eager and anxious to help transform organizations into equitable and inclusive cultures. Believe us, we’re in as much of a hurry to dismantle racism as anyone. But we know from experience that the process can’t be rushed. This human work can’t be accelerated with any particular programming, specialist, or checklist.

Read on to understand the reasons for the pace of our work, the deep focus on values, and the ultimate payoff.

You Can’t Skip Right to Action

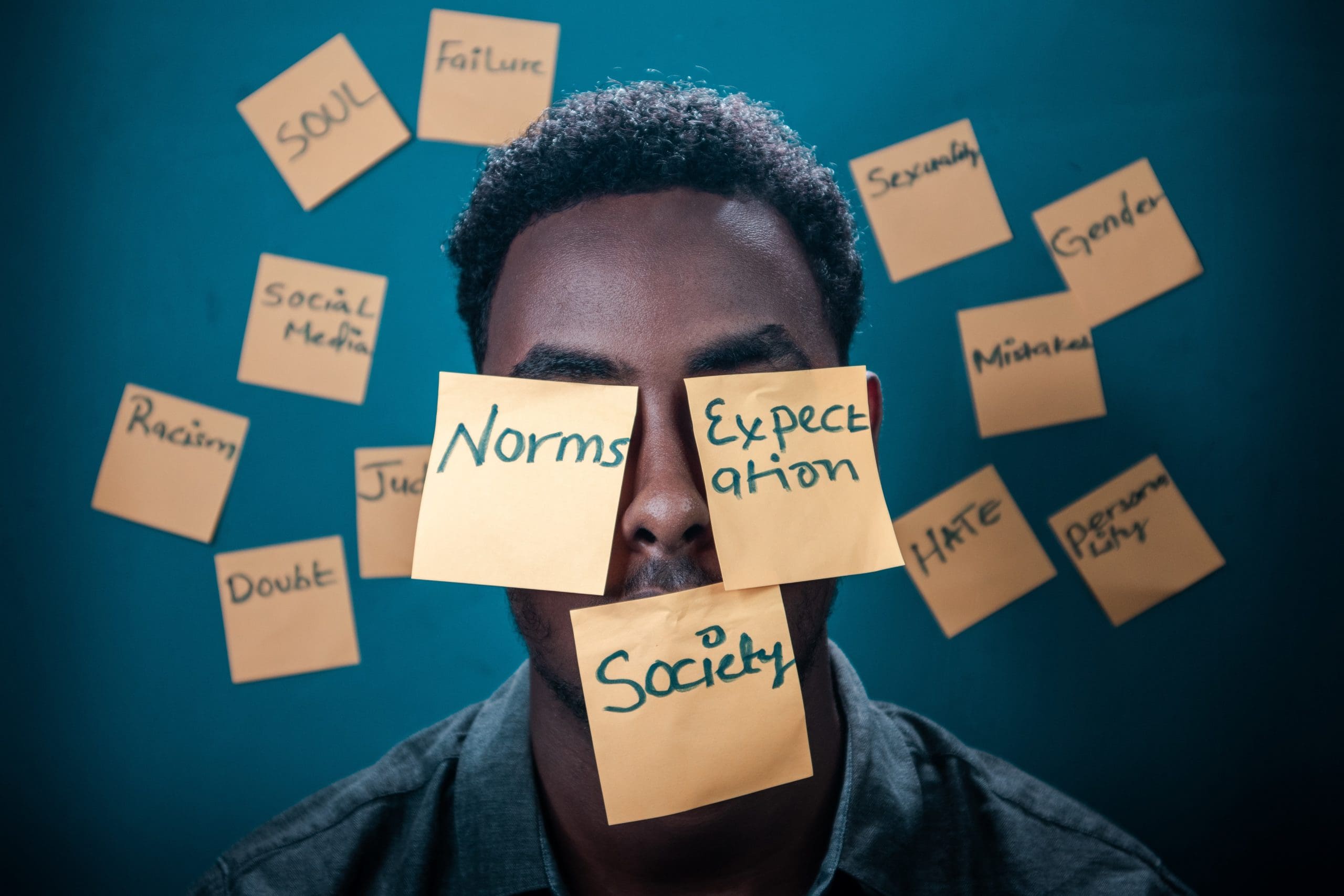

The image below is a graphic representation of the Cycle of Liberation, which shows the “cycle-like traits that characterized the socialization process that teaches us our roles in oppression.”

There are, as you can see, many points of development along this cycle. It’s not a quick path from “waking up” to “creating change.” But what we very often see is a desire to jump to creating change immediately, without doing the hard work of the other stages.

Our culture is biased toward action. We want to get things done, we need to feel productive, and we are desperate for measurable results. One of the dangers of this need for action is failing to discern what kind of action you’re taking, and if it really matters.

Joy likens this to wanting to call yourself a runner vs. actually running.

“Change is hard and messy. When you become aware of how you have been viewing the world vs. how you want to view the world, it’s really uncomfortable. And because we want to immediately stop the discomfort, we end up avoiding the real, hard work.

It’s like running. You can aspire to run a marathon the same way you aspire to be equitable and inclusive. You can have a vision of who you’d like to be. But when that vision starts to require daily exhaustion, shin splints, blisters, dizziness, headaches, and soreness, suddenly we want this to just be easier.

A common response is for people to start doing other things that are less hard, just so they can say they’re ‘taking action.’ Rather than just going for the run, they’ll buy the latest shoes or Apple watch, set up a running calendar, and download an app. It feels like you’re doing something, but you’re not actually creating change for yourself.

But then there are folks who can tap into their inner agility and say, ‘I’ll ice my shins. I’ll take Aspirin. I’ll rest and hydrate. I’ll push through.’ DEI teaches folks to stop saying, ‘This is hard so there must be something wrong with me,’ and realize instead that discomfort is a normal part of the process. There’s nothing wrong with you if you’re confused or frustrated or afraid.”

A runner isn’t someone who finished a race. A runner is someone who runs.

What Real Accountability Looks and Feels Like

Spoiler: it’s uncomfortable.

Another danger in moving prematurely to action is leaping to identify the “problem” without adequate self-reflection. Because no one wants to see themselves as part of the problem, people often project it onto others. Or they dump the responsibility for change onto the DEI individual or team.

We can’t have equity or inclusion without everyone first owning their behaviors.

Take the recent conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd. The guilty verdict was certainly a step toward accountability. But one conviction is the easy part. What’s much harder is looking at the way we are all accountable for George Floyd’s death, for police training, police brutality, racially divided police departments, and police spending on military-grade weapons.

In other words, we can’t see Derek Chauvin as just one bad officer. What we have is a systemic problem. Lest we think changing the police is an impossible task, consider the way The Atlantic describes the aviation industry’s response to any plane crash:

“The most constructive way that the federal government responds to avoidable loss of life is arguably in its treatment of aviation. Whenever a plane crash occurs, big or small, headline-grabbing or obscure, a team of experts is dispatched to reconstruct exactly what happened. The aim isn’t to advance a legal process or punish wrongdoers, but to figure out which changes, if any, could prevent it from happening again. Aviation is safe in large part because it learns from its disasters.”

So yes, waking up to injustice is crucial for us all. But real change starts with the internal dismantling of our privilege, beliefs, and collusion.

Aubrey, a former attorney, likens the internal work to law school.

“Law school doesn’t teach you to be a lawyer. It teaches you to think like a lawyer. Learning to think this way changes the way you see things. It changes the way your brain works. And suddenly everything looks different to you. Only then do you get out of law school and actually get to practice.

We see this kind of thinking transformation in the DEI world when people realize what they thought was a simple convenience has actually been a privilege that someone else isn’t getting. Or when they realize what it means to compliment a Black person on being ‘articulate’ or an Asian American for not having an accent. Or it’s realizing that trying to be colorblind is willfully refusing to see someone’s whole identity.

People may not have thought about these things before because they didn’t have to. But when they start engaging in DEI work, everything starts to look different. And it’s natural that people feel panic or guilt or just cognitive dissonance with what they’ve been taught to think. They feel confused, they don’t know how to react, they don’t know how to move forward.”

MJ adds that emotional resilience is what helps us through the cognitive dissonance.

“A common response to cognitive dissonance is clinging to what’s already familiar or known. People crave certainty and want to retreat to that space. They might scramble for data that supports their old worldview—a form of confirmation bias. They might dismiss their cognitive dissonance as an anomaly, rather than sitting with the discomfort and uncertainty until they figure out a pattern or a history.

I was working with a facilitator recently and doing the hard work of trying to understand why I behave in a certain way under certain circumstances. The facilitator said to me, ‘You could spend your time trying to figure out why, but maybe your time could be better spent identifying how you would like to behave instead.’ It reminded me that DEI work is all about aligning decisions and behaviors with your deepest values and getting off autopilot.”

Moving toward Others

According to Harro’s Cycle of Liberation, we can’t bring ourselves to act for change until we connect with others. There is no skipping the work of reaching out or building community. We don’t just tell our clients this. We have to show them.

Connecting with others begins by connecting with yourself. When we start to unpack white supremacy culture, people with traditionally privileged identities realize the harm that has been inflicted on them as well. They realize they aren’t thriving under perfectionism or binary thinking or power building. No one does.

And then there’s the connection we facilitate in deep listening sessions. We do this at the beginning of every engagement, regardless of the size or needs of the organization. Giving people a safe container to bring their full selves and making them feel seen is transformative. Clients call these sessions an oasis in the desert. They learn things they never knew about their colleagues. They share things they’ve never shared before. Their stories are welcomed, as are their feelings, challenges, desires, and limitations. Connection, they all realize, feels good. It’s what we were built for and what we need.

This is the moment when DEI work can begin—when everyone’s humanity is allowed to emerge.

If you or your organization is ready to lean into discomfort and get connected, contact anyone on our team today.